NewsDec | 3 | 2024

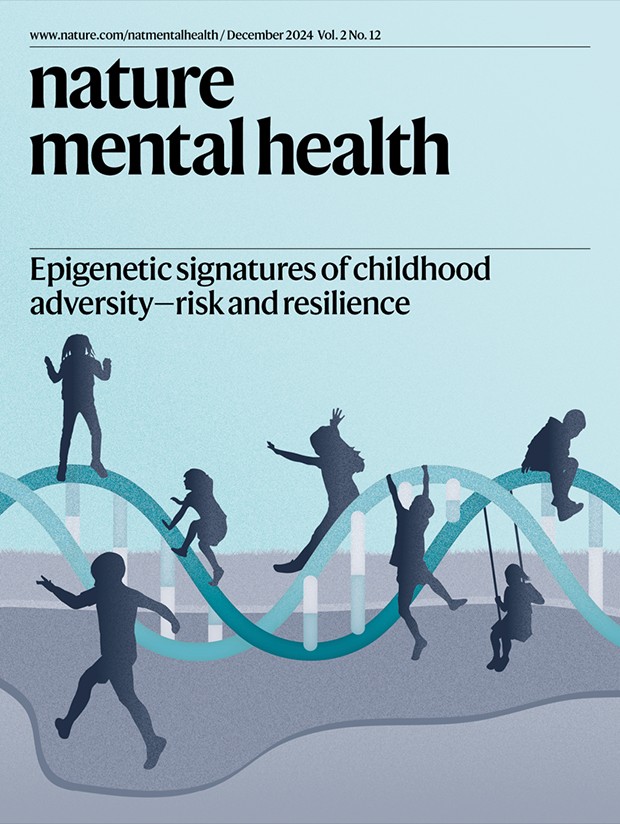

How Childhood Adversity Could Shape Mental Health and Resilience in Adulthood

Could early-life childhood adversity such as trauma, socio-economic hardship, or parental illness have an impact mental health and resilience later in life?

The answer is more complicated than you might think.

A new study published in Nature Mental Health by Alexandre Lussier, PhD, an investigator in the Center for Genomic Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Erin Dunn, ScD, formerly a principal investigator at the Center for Genomic Medicine (now at Purdue University), takes a closer look at the complex relationship between childhood adversity, changes in epigenetic marks, and risk of depression or other health conditions.

Epigenetics refers to a collection of mechanisms that control how genes are turned on and off. Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, can be compared to the dimmer switch on a lightbulb that finely controls how much light is emitted.

Research has shown that life experiences can leave lasting biological memories through changes in these epigenetic patterns, which can potentially influence later health outcomes.

The new findings by Lussier, Dunn and team suggest that changes in DNA methylation could serve as both a biomarker for identifying individuals at risk of depression and a possible marker of biological resilience against mental illness.

By shedding light on the different biological pathways connecting early adversity with mental health outcomes, the results may inform future strategies for intervention and the development of targeted therapies to prevent incidences of mental illness among people exposed to childhood adversity.

We talked to Dr. Lussier to learn more about the study and his research into the relationship between early childhood experiences and risk of depression later in life.

What motivated you to perform research in this field?

Depression is a highly common, costly, and disabling psychiatric condition, affecting nearly 12% of adolescents and 16% of adults in the United States.

One of the major risk factors for depression is exposure to childhood adversity, which can more than double the risk of depression later in life.

Although little is known about how this lifelong risk becomes embedded at a biological level, epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation (a way cells control which genes are turned on or off), have been suggested as a potential biological bridge between early-life environments and mental health.

I was drawn to this field because of its potential for real-world impact and the opportunity to address important gaps in our understanding of mental health.

I have always been interested in the biological mechanisms that influence and predict health because of my background in biochemistry and genetics.

Since epigenetics serve as a link between our genes and the environment, they offer a unique way to study how early-life experiences can impact health across the life course.

Thus, by investigating how childhood adversity becomes biologically embedded, I hope to contribute to new strategies for identifying at-risk individuals and developing and testing new strategies to reduce the burden of mental illness.

What have you found in the last couple of years?

For the past few years, I have worked as a postdoctoral fellow and then instructor in the lab of Dr. Erin Dunn, a former investigator at Mass General who is now a professor of Sociology at Purdue University.

Dr. Dunn and I have published multiple papers showing that childhood adversity leaves lasting biological memories on the genome, specifically through changes in DNA methylation.

For instance, in a previous paper our team published in Lancet Child & Adolescent Health (2023), we found that the effects of childhood adversity were particularly strong when they occur during sensitive periods, primarily between the ages three to five years.

These findings suggested this early childhood period is a potential window of opportunity for interventions that can reduce the impact of childhood adversity on future health.

We also found that epigenetic changes related to childhood adversity might be indicative of future health outcomes, with some of those changes related to risk for mental and physical illnesses such as depression and cardiovascular disease.

Overall, these findings have shown a potential role for epigenetic mechanisms in the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health.

What questions remain unanswered?

There is still a lot that scientists don’t know.

No studies have investigated whether changes in DNA methylation patterns explain the link between adversity and increased risk for depression.

Most studies generally assume epigenetic changes resulting from childhood adversity are bad, but this has never been demonstrated on a larger scale.

This knowledge gap limits our ability to design studies that leverage epigenetic patterns as biomarkers for depression and other health conditions related to childhood adversity.

Can you explain the findings of your latest paper?

In this latest study, we explored whether changes in epigenetic patterns, measured from blood, could explain why children who experience adversity early in life are more likely to develop depression as teenagers.

Using data from a large birth study in the UK, we found that changes in DNA methylation could explain up to three quarters of the connection between childhood adversity and depressive symptoms in early adolescence.

The findings suggest that these epigenetic changes might be one way that early-life stress becomes embedded in the body to affect mental health later in life.

One of the most interesting findings from this most recent paper is that not all of these DNA methylation changes were linked to a higher risk of depression.

In fact, a little more than half of them were related to resilience. In other words, the children exposed to adversity who had those epigenetic changes were less likely to have depressive symptoms.

These findings suggest that epigenetic mechanisms could help us understand not only who might be at risk for depression, but also who might be more resilient to exposures of early-life adversity.

What are the next steps and/or clinical implications of your findings for the future?

Additional studies are needed to replicate these findings across more diverse populations and across development, especially considering our recent work showing DNA methylation patterns linked to adversity can change over time.

If confirmed, these epigenetic markers could serve as biomarkers of risk and resilience for mental illness throughout the lifespan.

From a broader perspective, this work could lay the foundation for new strategies and tools to predict and prevent depression and other mental and physical disorders that can arise from exposures to childhood adversity.

Where do you see your research headed in the next five years?

Over the next five years, we plan to extend our research work to larger and more diverse datasets, since most of this work was completed in European-based populations, which limits its generalizability and interpretability.

Dr. Dunn has multiple projects exploring the role of childhood DNA methylation trajectories in mental health, as well as the biological embedding of positive life experiences.

Personally, I am also particularly interested to explore the potential role of epigenetic mechanisms as a marker or mechanism towards resilience for child and adolescent health.

Multiple lines of evidence from our work suggest DNA methylation might play a role in buffering the deleterious effects of childhood adversity, so I am excited to further explore the biological pathways that increase resilience and well-being among people who have experienced early-life adversity.

Alexandre Lussier, PhD

Investigator, Center for Genomic Medicine

Learn More

You can read the full paper, published in Nature Mental Health, here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44220-024-00345-8

Or you can check out our research briefing, which summarizes our main findings, here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44220-024-00346-7

Type

Centers and Departments

Topics

Support Research at Mass General

Your gift helps fund groundbreaking research aimed at understanding, treating and preventing human disease.

Check out the Mass General Research Institute blog

Bench Press highlights the groundbreaking research and boundary-pushing scientists working to improve human health and fight disease.